金牌会员

- 音乐币

- 0

- 贡献

- 0

- 金钱

- 3668

- 威望

- 0

- 相册

- 0

|

马上注册,结交更多好友,享用更多功能,让你轻松玩转社区。

您需要 登录 才可以下载或查看,没有帐号?注册

x

IPB Image

内容介绍:

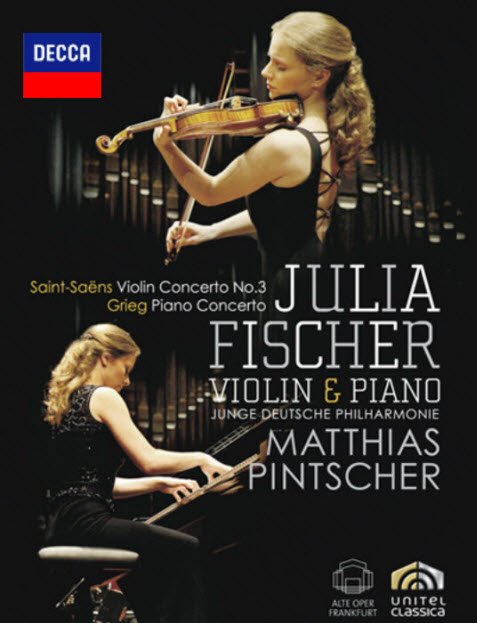

音乐史上鲜少可同时以小提琴家与钢琴家双重身份,於同一场演奏会上演出两首协奏曲的音乐家。以往有关小提琴家费雪的钢琴造诣极佳的讯息时有所闻,乐迷们却始终无从验证,但在这场2008年於德国举行的新年音乐会中,她先后演奏了圣桑的第三号小提琴协奏曲和葛利格的钢琴协奏曲,精彩的演出,充分证实自己在这两项乐器上的杰出造诣。

这份录影便是收录自2008新年音乐会的现场,也由於是现场演出,不可能经过剪辑修正错误,费雪在钢琴上的出色表现,确实令人印象深刻。这场在德国法兰克福老歌剧院的演出,让世人见识了费雪在小提琴以外的音乐才华,现场的观眾无不讚嘆。她於2010年同时发行了帕格尼尼二十四首小提琴奇想曲录音,是史上少数挑战这套艰难曲目的女性小提琴家,就连慕特、韩黛儿、莫莉妮等世界级名家也都瞠乎其后。而在这之前,她更已灌录过巴哈的无伴奏组曲和奏鸣曲,以及柴可夫斯基与布拉姆斯的小提琴协奏曲。才二十七岁,便已经是法兰克福音乐院的小提琴教授,这样一位传奇人物的艺术,当然值得仔细品味一番。

JULIA FISCHER’S DIONYSIAN VITALITY

Julia Fischer says she knew from an early age that she wanted to be a musician. She took up the violin because, when she was a child, she always had to wait until her mother and her brother (who is four years older than her) had finished practising on the family’s only piano. But she didn’t make a definite commitment to one instrument or the other. From the age of four she received piano lessons from her mother and applied herself at the keyboard with nearly the same intensity she brought to playing the violin. Finally, at the 2008 New Year’s Concert in Frankfurt’s Alte Oper, with the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie under Matthias Pintscher, the internationally celebrated violinist fulfilled one of her fondest wishes, playing not only the Violin Concerto no. 3 in B minor by Camille Saint-Sa?ns, but also, after the interval, Edvard Grieg’s famous A minor Piano Concerto. Julia Fischer, who was appointed a professor — Germany’s youngest — at Frankfurt’s University of Music and Performing Arts in 2006, has long ranked among the great violinists of her day. A pupil of Ana Chumachenko, she won the Yehudi Menuhin Competition in the master’s presence at the age of eleven, and then took first prize at the Eurovision Competition for young instrumentalists. Other awards followed.

“Being a soloist is very much a matter of having a particular temperament and unshakeable self-confidence. The qualities required differ from those needed to be a first-rate concertmaster, who has, first and foremost, to really enjoy being a colleague and ensemble player rather than a strong, independent-minded leader who likes taking risks.” Thus Isaac Stern. Goodness knows, Julia Fischer has that special temperament, whether she’s playing Bach or Elgar, Schumann or Schnittke, Schubert or Hindemith, and it motivates her to bring out the heterogeneity within and between different pieces of music.

“Unshakeable self-confidence”: Anyone who gets to know Julia Fischer personally encounters a clear-thinking and straight-talking young woman. Her self-confidence becomes even more apparent on the concert platform. She knows no fear in tackling the weightiest concertos in the repertoire, such as those by Beethoven, Brahms and Sibelius, and her fearlessness feeds that crucial intensity, without which a concert would seem lacklustre.

Some listeners mistakenly equate concentration and technical perfection with coldness, detachment or mere diligence. But exploiting music as a vehicle for one’s own emotions, important though one may feel them to be, is equally misguided. Julia Fischer’s self-confidence derives from musical sources. She doesn’t study works only on the violin; her exceptional facility on the piano enables her to explore orchestral scores at the keyboard as well, or to probe Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata through the piano as well as the violin part. Her music-making is thus symphonic in spirit: she knows how much weight and just what role the violin has in the works she plays. That, of course, also applies to her performance of the Grieg Piano Concerto. Hers is a collaboration with orchestral musicians in the truest sense of that word.

A solo player has to be independent-minded, according to Isaac Stern. Learning and studying stop when an artist steps onto the concert platform. There she is on her own and has to make the best of it, regardless of how memorably other great violinists may have interpreted the Bach Chaconne, the Tchaikovsky Concerto or Mozart’s violin works. When Julia Fischer performs, there is only the presence of this enchanting young musician. Her playing is accountable to no-one else. She imitates no-one, not even herself.

Spirited, self-confident, independent: Julia Fischer is all of these things, and she also exemplifies the last of Isaac Stern’s conditions, delight in risk-taking — the strength to seize the moment, to find that elusive element of spontaneity, no matter what the acoustic, her fellow-musicians or the audience might be like. Were she not prepared to take risks, she would not have appeared on the same evening as both violinist and pianist, effectively competing with herself. The soloist must value the imponderable as an emboldening source of momentary inspiration. To enjoy taking risks also means captivating every listener, pushing oneself to the limit in order to convince and compel, as Julia Fischer succeeds so enthrallingly in doing. Stern referred to the personality of a “leader”. It seems doubly remarkable that even a very young soloist can possess and radiate this defining power and sovereignty.

Consider the way Fischer begins the Sibelius Concerto: dreamily, almost trance-like, in order then to spin out the exposition’s expressive line broadly and with vehemently increasing intensity. There is one passage in the first movement’s exposition which is commonly misunderstood as a drivingly virtuosic entry. Julia Fischer, by contrast, articulates the harmonic and dramaturgical structure of this passage without allowing it to be degraded into something flashy and mechanical. And in the Adagio di molto she is able to mould the great build-ups into a breathtaking giant arch.

Julia Fischer’s playing is marked by poise, technical mastery, passion, sensitivity and an exceptional richness of colour. She can build an imposing musical edifice from the Chaconne in Bach’s D minor Partita. In her hands, Mozart sonatas become intimate dialogues, whereas she approaches Schubert with a touching mixture of dazzling virtuosity and poignant melancholy. She turns Grieg’s Third Violin Sonata into a dramatic descent into realms of darkness, danger and foreboding.

This and more Julia Fischer accomplishes, not only by virtue of her temperament, self-confidence, independence and risk-taking but, above all, by means of her highly individual tone, characterised by a Dionysian sensuousness and dark-hued earthiness. Its distinctiveness ultimately is the starting-point and basis of her already unique career. Everything she plays has profundity and vitality, everything is clear in articulation and intonation. Whether in New York, Chicago, Tokyo or Berlin, her performances are acclaimed for a lack of “attitude” that allows the music’s logic and sensuous qualities to unfold with great serenity. That holds true for her interpretation of the Saint-Sa?ns, which challenges the frequent misconception that this concerto is no more than a zippy, lightweight virtuoso showpiece. Instead she finds the music’s nobility and elegance and infuses them with gripping passion. Suddenly the concerto is revealed in all its brilliance and rhythmic delicacy, its sophisticated sonorities sounding as fresh and new as on the day it was composed. The Junge Deutsche Philharmonie under the direction of composer–conductor Matthias Pintscher brings to the work a corresponding degree of involvement and ardour.

Exploring the world of music and channelling it in performance requires a fully rounded artistic life, organised as thoughtfully and intelligently as Julia Fischer’s. So why not also demonstrate what she has to say at the piano? Lo and behold, Fischer here is every bit as serious: she plays the Grieg Piano Concerto in the same symphonic spirit, with the same courage and the same compelling force — in other words, with everything that has captivated the world when she plays the violin.

Harald Eggebrecht

5/2010

【引用】New York Times

Julia Fischer in her other guise as a pianist.

By ANTHONY TOMMASINI

Published: October 29, 2010

FOR a demonstration of comprehensive musicianship and instrumental mastery, few artists have topped the performance that the German violinist Julia Fischer gave at the Alte Oper in Frankfurt on Jan. 1, 2008.

Ms. Fischer, then 24, played a dazzling account of Saint-Sa?ns’s Violin Concerto No. 3 with the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie, conducted by the inventive composer Matthias Pintscher. What made the concert momentous was that after intermission Ms. Fischer returned as a pianist and gave an accomplished, beautifully personal performance of Grieg’s Piano Concerto.

Ms. Fischer has played the piano along with the violin since childhood, though mostly for her own pleasure. She had never before put her skills as a pianist on public display like this. Now Decca has released a DVD of the concert.

Ms. Fischer’s achievement here places her in select company. Long ago it was common for musicians to be trained on more than one instrument, though even then most performers eventually made a choice.

Mozart could have had a dual career playing piano and violin. But from his early 20s he typically played the violin (and the viola, which he loved) in chamber music sessions, while the piano was his calling card on the concert stage. Of course Mozart had other things to keep him busy.

More recently many performers have played secondary instruments on the side, but few have played more than one in public. The colossal cellist Mstislav Rostropovich sometimes accompanied his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya, at the piano. Their specialty was Mussorgsky’s cycle “Songs and Dances of Death.” Still, as a pianist Rostropovich mostly played the song repertory, not the Brahms concertos.

Quite a few top-notch conductors have been active pianists, including Michael Tilson Thomas and James Levine. Leonard Bernstein made some wonderful recordings of Mozart piano concertos, Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” Schumann’s Piano Quintet and other works. The formidable British composer Thomas Adès, a skilled conductor, is an excellent pianist who gave one of the year’s most imaginative recitals this spring at Carnegie Hall. Yet with all due respect to the technical demands of conducting, most maestros would concede that this lofty art does not require the kind of specialized skill needed to play an instrument.

Some great singers first got into music through playing an instrument. The beloved mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, who died in 2006, was a successful violist when, at 26, she began studying voice. And her incomparable singing was like an extension of her viola playing in its directness and elegance.

At one time conservatories expected instrumentalists to develop proficiency in a secondary instrument, though most institutions seem to have dropped this requirement. Even so, all it meant was that a clarinetist had to be able to play, say, a Bach invention on the piano, not the Grieg concerto. To play a second instrument at a high level, as Ms. Fischer does, demands impressive versatility.

Growing up in Munich, Ms. Fischer was first drawn to the piano, as she explains in an interview on the DVD. But her mother, a pianist, and her older brother had first dibs on the piano in the house. Her mother, thinking it might be nice to have a violinist in the family, encouraged her to take violin lessons too. When, at 12, Ms. Fischer won the Menuhin Competition her path seemed clear: she was a violinist.

The idea of performing the Grieg concerto arose in 2006. It is a work Ms. Fischer grew to love as a child from listening to a recording by Sviatoslav Richter.

For nearly two years she fit in as much piano practicing as she could while continuing to play some 90 concerts a year as a violinist. She was careful, she explains in the interview, not to strain her hands by playing the piano too much or too strenuously. The piano requires more physical strength, she says, and leaves her feeling less flexible.

She went forward with the plan to play the Grieg with the hope, she says, that the audience members, the players of the youth orchestra (ages 18 to 28) and Mr. Pintscher (who has written a violin concerto for her) would “forgive my mistakes.”

She does not make many in the honest and articulate performance captured here. Cascades of descending double thirds and bursts of double octaves are deftly rendered. The roiling first-movement cadenza is both poised and impassioned. That she is used to spinning melodies on a violin comes through in the poignant way she shapes ruminative solo lines in the slow movement. She brings punchy crispness and fiery excitement to the finale.

Though she has received other offers to perform as a pianist (the conductor Yakov Kreizberg, with whom she has recorded several violin concertos, wants her to play Mozart piano concertos with him), Ms. Fischer has so far declined. Besides her career as a violinist, she is a professor at a college of music in Frankfurt and the mother of a 1-year-old son.

Today, at 27, when she plays music for pleasure at her home near Munich, she always plays the piano. If Ms. Fischer does not play the piano in public again, at least she has had this triumph. On the DVD, during the Grieg cadenza, a violist from the orchestra can be seen looking in awe at Ms. Fischer. These young musicians know how hard it is to play just one instrument, let alone two.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/31/arts/mus...tml?_r=0

【引用】 This DVD features Julia Fischer performing Saint-Saens' Violin Concerto no. 3 as well as Grieg's Piano Concerto on the same concert. Filmed live on New Year's Day 2008, this concert marked the professional debut of Julia Fischer as a concert pianist. In his review of this concert Arno Widmann of the Frankfurter Rundschau newspaper described the atmosphere in the concert hall: "The excitement of the audience was palpable. After all, everyone was aware that only two extremes were possible: either this would turn out to be the total disgrace of one of the greatest living violinists; or it would mark the triumphant birth of a new pianist. From the beginning of the Adagio of the Grieg piano concerto, everyone present knew they were witnessing the overwhelming triumph of Julia Fischer."

Production Engineer: Ralf Happel

Recording Engineer: Christian Feldgen

Assistant Engineers: Julia Havenstein, Michael Nitschke

Sound Editing: Caroline Siegers

Sound Mix & Audio Producer: Peter Hecker

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS:

Menus: English

Picture Format: 16:9 Anamorphic Widescreen

Region Code: 0 (worldwide)

DVD Format: NTSC

Duration: 62 mins (concert); 35 mins (interview)

Sound: 1 LPCM Stereo, 2 DTS 5.1 Surround (concert)

Subtitles: English, French, Spanish, Chinese (interview)

R E V I E W:

SAINT-SA?NS Violin Concerto No. 3. GRIEG Piano Concerto ? Julia Fischer (vn, pn); Matthias Pintscher, cond; Junge Deutsche P ? DECCA 074 3344 (DVD: 61:02 Text and Translation)

& Julia Fischer—Two Musical Worlds (47:50)

Cory Cerovsek, prodigious violinist, pianist, and mathematician, would play a violin concerto and a piano concerto on the same program (he didn’t, so far as I know, solve equations while doing so). Julia Fischer, by way of comparison, has only two arrows in her quiver. And in her program from January 2008 with the Junge Deutsche Philharmonie she lets them both fly, playing Saint-Sa?ns’s Third Violin Concerto and following with Grieg’s Piano Concerto after the intermission. Heifetz, Kreisler, and Grumiaux also played both instruments—reportedly well in the first two instances (recordings exist of both, but not playing repertoire) and demonstrably in recordings in the third (Grumiaux accompanied his own playing of violin sonatas by Mozart and Brahms). Did Grumiaux’s versatility raise him to a higher level in our estimation than Heifetz or Kreisler? Does Fischer’s?

In Saint-Sa?ns’s concerto, Fischer strops a sharp edge on the technical passages—occasionally, perhaps, to the point of brittleness—an impression reinforced by the cleanliness of the recorded sound (of both soloist and orchestra); almost clinical playing by the ensemble; the somewhat edgy tone of Fischer’s violin, tightly wound rather than bright in the middle registers and somewhat hoarse rather than lush on the G string; and her rapid, rather narrow vibrato. Fischer does vary the speed of that vibrato, slowing it down in the central movement, and even, here and there, stopping altogether, although she doesn’t seem to be striving for (or achieving) an effect so eldritch as Anne-Sophie Mutter’s in Beethoven’s works. In the second movement, she keeps the passages moving, without stopping to smell the flowers (and not offering them for her listeners’ olfactory pleasure, either). Listeners who admire Grumiaux’s warmth and Milstein’s nobility in this Andantino may reflect that while its atmosphere has been likened to that of a boat floating amid the reflected sunshine of a lake, Fischer’s reading recalls more vividly a motorboat in the same setting. Just before the harmonics that bring the movement to a close, Fischer winds down her vibrato to a virtual standstill (although she vibrates on the final harmonics themselves).

Fischer seems to throw the bow onto the strings and tosses her body backward, creating a very different visual impression than those of, say, Heifetz, Milstein, and Oistrakh (you could add the next generation, Menuhin and Ricci). Her playing seems most expressive in moments like the third movement’s chorale (of which the orchestra also gives a dynamically nuanced account). The recorded sound (offering DTS and LPCM 48 kH as choices) places her slightly forward.

Although Fischer looks a bit stiff at the keyboard, she establishes her command as soloist in the first movement’s opening measures. And she warms to the second theme’s expressivity—lingering perhaps more lovingly here than at any point in the violin concerto. She’s sonorous in the cadenza, but on the whole, perhaps, less flamboyant—and even a bit less dramatic—as a pianist than as a violinist. In the second movement, neither she nor the orchestra generate a particularly rich atmosphere, although she communicates the rhythmic vitality of the finale’s first thematic statement.

Those who wonder whether her piano playing has a sense of largeness and suppleness or merely seems clean and antiseptic might benefit from taking a further leap and comparing the violin playing to the piano playing: One sheds light on the other. Would a pianist at this level who hadn’t achieved a reputation as a violinist have been offered the opportunity to record Grieg’s Concerto? Jack Benny played the violin, and his celebrity (coupled of course with his generosity in raising money for struggling orchestras) led to bookings. But nobody, least of all he himself, pretended that he was playing well. It was a stunt.

In the interview, Fischer remarks—perhaps tellingly—that when she wants to play for pleasure, she plays the piano, which she began practicing again in earnest several years ago. She explains the choice of repertoire and remarks on the differences in playing the two instruments (the piano, she maintains, demands greater strength but leads to less flexibility). She worries aloud about “wrecking” her hands. She also notes the different way in which the violin and piano interact with the orchestra. Then she begins to ponder imponderables like spirituality, education, home, and future. Clips show her teaching the last measures of Kreisler’s Praeludium and Allegro and Saint-Sa?ns’s Havanaise.

A demonstration of sublime inspiration or a stunt? In the course of the interview, Fischer suggests that her talent isn’t unnatural but a natural product of work and experience. So much, I guess, for sublime inspiration. Recommended most strongly to those who find this kind of versatility fascinating and appealing; recommended less strongly—though still recommended—to those who find it merely tolerable.

IPB Image

IPB Image

专辑曲目:

01. Opening titles ? Générique ? Vorspann

CAMILLE SAINT-SA?NS (1835–1921)

Violin Concerto no. 3 in B minor, op. 61

si mineur ? h-Moll

02. I Allegro non troppo

03. II Andantino quasi allegretto

04. III Molto moderato e maestoso – Allegro non troppo

EDVARD GRIEG (1843–1907)

Piano Concerto in A minor, op. 16

la mineur ? a-Moll

05. I Allegro molto moderato

06. II Adagio –

07. III Allegro moderato molto e marcato –

Quasi presto – Andante maestoso

08. Closing credits ? Générique ? Nachspann

The DVD includes an extensive interview with Julia Fischer, who candidly discusses her life, art, and music (in German, with multi-language subtitles).

下载地址:

|

|

|小黑屋|手机版|Archiver|版权声明|001科技|

音乐吧 52290

( 桂ICP备2021006182号 )

|小黑屋|手机版|Archiver|版权声明|001科技|

音乐吧 52290

( 桂ICP备2021006182号 )